The Latest from Boing Boing |  |

- Render frosted glass transparent with Scotch tape

- Steampunk Venetian mask

- International Space Station improv sitcom

- PUPPY vs. YPPUP

- Cigar box guitar tribute to Blind Willie Johnson: free MP3 album

- Cadbury Egg inside chocolate cupcake

- Videos of kids who are terrified by the Easter Bunny

- Android secretly stores location data too -- though less of it, and with less detail

- Two cool new kits from Make

- Clown-suited blackmailer convicted

- Obama declares Bradley Manning guilty

- Choral work based on Robert Frost poem repurposed after copyright problems

- No-Spill Gas Can

- How journalists uncovered earthquake risks in California's schools

- Room-sized spirograph

- Science and Zombies

- Citizen science in the Gulf of Mexico

- Elk calf frolics in a puddle

- Portal turret Easter egg

- Just in time for Earth Day: The worst Earth Day press releases

- A demographically representative congress

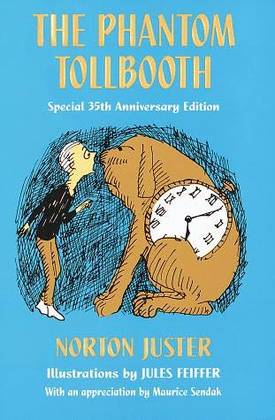

- Michael Chabon's introduction to The Phantom Tollbooth 50th anniversary edition

- Meet Science: What is "peer review"?

- Gigantic papercraft Audi

| Render frosted glass transparent with Scotch tape Posted: 22 Apr 2011 10:36 PM PDT YouTube user TheFarmacyMan discovered that his workplace frosted glass privacy screen could be rendered transparent by applying a piece of Scotch tape to it. A useful detail for anyone planning a caper novel or a robbery. A user called rawnoodles10 posits "..the glue on the tape fills in the small imperfections on the surface of the glass. Since the glass, the glue, and the tape are clear, filling in the imperfections (the frosting) makes the glass clear." Weird Tape Effect (via Core77) |

| Posted: 22 Apr 2011 10:15 PM PDT  Loving steampunk mask-maker Bob Basset's foray into goggled-out Venetian carnival masks. Loving steampunk mask-maker Bob Basset's foray into goggled-out Venetian carnival masks. |

| International Space Station improv sitcom Posted: 23 Apr 2011 12:55 AM PDT Johannes from Monochrom sez, "This is the 2nd episode (and frickin' good one) of Monochrom's ten-part improv-reality-sitcom about living and working on the International Space Station. The four actors playing the ISS crew must develop strategies on the fly in response to surprise situations, which are loosely based on actual ISS data uncovered by Monochrom. In space no one can hear you complain about your job. This episode was recorded in front of a live audience on April 15, 2011." Monochrom's International Space Station Sitcom: Episode 2 (Thanks, Johannes!) |

| Posted: 21 Apr 2011 03:08 PM PDT |

| Cigar box guitar tribute to Blind Willie Johnson: free MP3 album Posted: 22 Apr 2011 02:01 PM PDT  A gift from my friends at Cigar Box Nation: a cigar box guitar tribute to Blind Willie Johnson. |

| Cadbury Egg inside chocolate cupcake Posted: 22 Apr 2011 01:31 PM PDT |

| Videos of kids who are terrified by the Easter Bunny Posted: 22 Apr 2011 01:19 PM PDT

Tara McGinley at Dangerous Minds presents us all with "an early Easter gift of some YouTube videos of children who are absolutely terrified of the Easter Bunny." "You know what?," she adds, "He scared the crap out of me, too." Link to videos. Not suitable for children or adults who are scared by the Easter Bunny. |

| Android secretly stores location data too -- though less of it, and with less detail Posted: 22 Apr 2011 12:42 PM PDT Magnus Eriksson has located a trove of detailed location history stored by Android phones that is very similar to the one stored by iOS devices. The Android file is a little harder to extract, but it isn't encrypted, and would be just as vulnerable to a phone thief, forensics expert, or malicious software as the iOS file. Like iOS, Android stores these databases in an area that is only accessible by root. To access the caches, an Android device needs to be "rooted," which removes most of the system's security features. Unlike iOS, though, Android phones aren't typically synced with a computer, so the files would need to be extracted from a rooted device directly. This distinction makes the data harder to access for the average user, but easy enough for an experienced hacker or forensic expert.Android phones keep location cache, too, but it's harder to access |

| Posted: 22 Apr 2011 11:49 AM PDT The new issue of MAKE is out (Vol 26), and in addition to a bunch of cool how to projects, we are also offering two new kits based on projects in this issue.

Our Pendulum Challenge Kit ($25.99) includes everything you need to make the project featured in Make, Volume 26. At the heart of the system is a pre-programmed PIC micro controller that runs the internal state machine which processes the game's switch inputs and drives its LED outputs. The game's most distinct feature is its array of 15 LEDs (14 red and 1 green), arranged in the shape of an arc to simulate the path of a swinging pendulum. For added sound effects, the game has a piezo buzzer.

Our Galvanic Skin Response Kit ($24.99) includes everything you need to make the truth meter circuit featured in Make Volume 26. See what happens when someone asks you questions or when you laugh or get surprised. Everyone responds differently. See if you can turn the LED on with your mind. Try it on your friends, acquaintances, or adversaries. It's a great way to get to know someone!Galvanic Skin Response Kit | Pendulum Challenge Kit |

| Clown-suited blackmailer convicted Posted: 21 Apr 2011 11:21 PM PDT A man has been convicted of extortion in a bizarre scheme that involved collecting the loot while wearing a clown suit and riding a miniature bicycle. Frank Salvador Solorza targetted his immigrant cousins in Redwood City, sending letters and calling them, posing as an immigration officer who threatened to deport them unless they paid him $50,000 to ensure that their papers "would be good forever." The family called the police, who worked with them to arrest the blackmailer, who called and told them that the money would be collected by "a man in a clown suit and riding a small bicycle." Solorza was arrested after picking up a bag which he believed contained $50,000, wearing "a clown suit, a clown glitter wig, a Pirates of the Caribbean hat (complete with dreadlocks), and sunglasses." He was riding a small bicycle. He was carrying a receipt for the outfit from the House of Humor costume store in Redwood City. Perhaps he intended to return it after the caper. Blackmailer in a clown suit gets 3 years (via Lowering the Bar) (Image: Clown, a Creative Commons Attribution (2.0) image from chris-rice's photostream) |

| Obama declares Bradley Manning guilty Posted: 22 Apr 2011 11:29 AM PDT The President and Commander-in-Chief says that Bradley Manning, accused military whistleblower, broke the law. OBAMA: So people can have philosophical views [about Bradley Manning] but I can't conduct diplomacy on an open source [basis]... That's not how the world works. And if you're in the military... And I have to abide by certain rules of classified information. If I were to release material I weren't allowed to, I'd be breaking the law. We're a nation of laws! We don't let individuals make their own decisions about how the laws operate. He broke the law.Just so you know, |

| Choral work based on Robert Frost poem repurposed after copyright problems Posted: 22 Apr 2011 11:00 AM PDT Boing Boing pal Andrea James writes, "Interesting backstory. The original choral work "Sleep" was set to Robert Frost's 'Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening.' Then came the legal tussle. Eric Whitacre explains..." After a LONG legal battle (many letters, many representatives), the estate of Robert Frost and their publisher, Henry Holt Inc., sternly and formally forbid me from using the poem for publication or performance until the poem became public domain in 2038. I decided that I would ask my friend and brilliant poet Charles Anthony Silvestri ... to set new words to the music I had already written."So," Andrea writes, "Silvestri created a poem with the exact cadence of the Frost work. The result is this. I always love these kinds of crowdsourced art in response to these kinds of creative disputes!" |

| Posted: 21 Apr 2011 02:43 PM PDT  This No-Spill Gas Can has a push button spout that almost completely eliminates spilling gas when you fill a small fuel tank on a lawn mower or weed whacker. The first time I tried it, I filled a chain saw to exactly the spot I wanted. Since most chain saws have small and oddly-shaped tanks, I was really impressed. This No-Spill Gas Can has a push button spout that almost completely eliminates spilling gas when you fill a small fuel tank on a lawn mower or weed whacker. The first time I tried it, I filled a chain saw to exactly the spot I wanted. Since most chain saws have small and oddly-shaped tanks, I was really impressed.Most gas cans have an unreliable separate vent cap that you have to remember to open and close, and even worse, a leaky main cap that lets the gas vapor escape when you leave it in the sun and the tank can't hold the pressure. The No-Spill can has a single push button that controls both pouring and venting, and the only thing to remember is to push the button with the can level to relieve the pressure. (And don't make the mistake I did, and look into the nozzle, because you get a puff of gas fumes in your eyes. I'm lucky I wear glasses.) No-Spill also has a line of fuel cans that meet CARB (California Air Resources Board) requirements, and that are required in many states. I live in Ohio, and had never even heard of this requirement, though I'm aware that gas cans pressurize in the sun, and I make sure to keep them in the shade. -- Matthew Robbins No-Spill Gas Can

|

| How journalists uncovered earthquake risks in California's schools Posted: 22 Apr 2011 10:15 AM PDT The Center for Investigative Reporting's California Watch site has a really fascinating multi-part, multi-media report about problems with creation and enforcement of construction standards, which have left the State's public schools vulnerable to earthquakes. The report, itself, is great, but I wanted to highlight one aspect of this package that might otherwise go unnoticed. Included in the On Shaky Ground report is an interactive timeline documenting "the story behind the story". It's a great inside look at how journalism sausages get made—and how an assignment to write a short piece about the 20th anniversary of the Loma Prieta 'quake evolved into something much larger, and much more important. Via Allie Wilkinson |

| Posted: 22 Apr 2011 10:04 AM PDT Drawingmachine by Eske Rex from Core77 on Vimeo. I love the way this thing looks like a cross between some kind of medieval engineering project and the best playground equipment ever. Made by Eske Rex—a Swedish-born designer who'd never heard of the toy Spirograph—it's based on a piece of 19th-century technical equipment.

Via The Atlantic |

| Posted: 22 Apr 2011 09:37 AM PDT Science and zombies go together like, er, brains and more brains. Smithsonian has a nice round-up of different ways that researchers have used zombie myth to model scientific ideas, or turned scientific speculation on the zombie story. (Submitterated by SarahZ) |

| Citizen science in the Gulf of Mexico Posted: 22 Apr 2011 09:26 AM PDT If you live or vacation near the Gulf of Mexico, Talking Science has a nice suggestion: Join one of the citizen science projects that are helping researchers document the long-term environmental effects of last year's BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Submitterated by leharrist |

| Posted: 22 Apr 2011 09:32 AM PDT I feel like this elk calf accurately expresses my feelings about the fact that it is Friday. EDIT: This video is the work of nature photog David Neils. It's great stuff. Big thanks to smithemma for pointing out the video's creator! Submitterated, appropriately enough, by Koocheekoo |

| Posted: 22 Apr 2011 08:47 AM PDT |

| Just in time for Earth Day: The worst Earth Day press releases Posted: 22 Apr 2011 08:47 AM PDT Lord, won't you buy me a pair of recycled bamboo underpants? As someone who spent a lot of time hitting the "delete" button in my email the past couple weeks, I can thoroughly appreciate GreenBiz.com's third annual round-up of painfully Greenwashed press releases. It's a train-wreck of terrible Earth Day tie-in promotions, exhortations to save the planet by buying more stuff, and feeble attempts to make up for a year of being unsustainable. Just in time for Earth Day! (Via Sam Boykin) |

| A demographically representative congress Posted: 22 Apr 2011 08:30 AM PDT GOOD draws up a chart describing what a demographically representative Congress might look like. The short version appears to be that if hispanics and atheists ever insist on voting for hispanics and atheists, the Republicans are in trouble. |

| Michael Chabon's introduction to The Phantom Tollbooth 50th anniversary edition Posted: 21 Apr 2011 10:18 PM PDT Michael Chabon has written a special introduction for the fiftieth anniversary edition of Norman Juster's wonderful, classic kids' book The Phantom Tollbooth. As you might expect, it's a lovely piece of work. 'The Phantom Tollbooth' and the Wonder of Words (Thanks, Zack!) |

| Meet Science: What is "peer review"? Posted: 22 Apr 2011 08:02 AM PDT When the science you learned in school and the science you read in the newspaper don't quite match up, the Meet Science series is here to help, providing quick run-downs of oft-referenced concepts, controversies, and tools that aren't always well-explained by the media.  "According to a peer-reviewed journal article published this week ..." How often have you read that phrase? How often have I written that phrase? If we tried to count, there would probably be some powers of 10 involved. It's clear from the context that "peer-reviewed journal articles" are the hard currency of science. But the context is less obliging on the whys and wherefores. Who are these "peers" that do the reviewing? What, precisely, do they review? Does a peer-reviewed paper always deserve respect, and how much trust should we place in the process of peer review, itself? If you don't have a degree in the sciences, and you aren't particularly well-versed in self-taught science Inside Baseball, there's really no reason why you should know the answers to all those questions. You can't be an expert in everything, and this isn't something that's explicitly taught in most high schools or basic level college science courses. And yet, I and the rest of the science media continue to reference "peer review" like all our readers know exactly what we're talking about. I think it's high time to rectify that mistake. Ladies and gentlemen, meet peer review: What does the phrase "peer-reviewed journal article" really mean? This part you've probably already figured out. Journal articles are like book reports, usually written to document the methodology and results of a single scientific experiment, or to provide evidence supporting a single theory. Another common type of paper that I talk about a lot are "meta analyses" or "reviews"—big-picture reports that compare the results of lots of individual experiments, usually done by compiling all the previously published papers about a very specific topic. No single journal article is meant to be the definitive last word on anything. Instead, we're supposed to improve our understanding of the world by looking at what the balance of evidence, from many experiments and many articles, tell us. That's why I think reviews are often more useful, for laypeople. A single experiment may be interesting, but it doesn't always tell you as much about how the world works as a review can. Both individual reports and reviews are published in scientific journals. You can think of these as older, fancier, more heavily edited versions of 'zines. The same scientists who read the journals write the content that goes in the journals. There are hundreds of journals. Some publish lots of different types of papers on a very broad range of topics—"Science" and "Nature", for instance—while others are much, much more specific. "Acute Pain", say. Or "Sleep Medicine Reviews". Usually, you have to pay a journal a fee per page to be published. And you—or the institution you work for—has to buy a subscription to the journal, or pay steep prices to read individual papers. Peer review really just means that other scientists have been involved in helping the editors of these journals decide which papers to publish, and what changes need to be made to those papers before publication. How does peer review work? It may surprise you to learn that this is not a standardized thing. Peer review evolved out of the informal practice of sending research to friends and colleagues to be critiqued, and it's never really been codified as a single process. It's still done on a voluntary basis, in scientists' free time. Such as that is. And most journals do not pay scientists for the work of peer review. For the most part, scientists are not formally trained in how to do peer review, nor given continuing education in how to do it better. And they usually don't get direct feedback from the journals or other scientists about the quality of their peer reviewing. Instead, young scientists learn from their advisors—often when that advisor delegates, to the grad students, papers he or she had volunteered to review. Your peer-review education really depends on whether your advisor is good at it, and how much time they choose to spend training you. Meanwhile, feedback is usually indirect. Journals do show all the reviews to all of a paper's reviewers. So you can see how other scientists reviewed the same paper you reviewed. That gives you a chance to see what flaws you missed, and compare your work with others'. If you're a really incompetent peer reviewer, journals might just stop asking you to review, altogether. Different journals have different guidelines they ask peer reviewers to follow. But there are some commonalities. First, most journals weed out a lot of the papers submitted to them before those papers are even put up for peer review. This is because different journals focus on publishing different things. No matter how cool your findings are, if they aren't on-topic, then "Acute Pain" won't publish them. Meanwhile, a journal like "Science" might prefer to publish papers that are likely to be very original, important to a field, or particularly interesting to the general public. In that case, if your results are accurate, but kind of dull, you probably will get shut out. Second, peer reviews are normally done anonymously. The editors of the journal will often give the paper's author an opportunity to recommend, or caution against, a specific reviewer. But, otherwise, they pick who does the reviewing. Reviewers are not the people who decide which papers will be published and which will not. Instead, reviewers look for flaws—like big errors in reasoning or methodology, and signs of plagiarism. Depending on the journal, they might also be asked to rate how novel the paper's findings are, or how important the paper is likely to be in its field. Finally, they make a recommendation on whether or not they think the specific paper is right for the specific journal. After that, the paper goes back to the journal's editors, who make the final call. If a paper is peer reviewed does that mean it's correct? In a word: Nope. Papers that have been peer reviewed turn out to be wrong all the time. That's the norm. Why? Frankly, peer reviewers are human. And they're humans trying to do very in-depth, time-consuming work in a limited number of hours, for no pay. They make mistakes. They rush through, while worrying about other things they're trying to get done. They once had to share a lab with the guy whose paper they're reviewing and they didn't like him. They get frustrated when a paper they're reviewing contradicts research they're working on. By sending every paper to several peer-reviewers, journals try to cancel out some of the inevitable slip-ups and biases, but it's an imperfect system. Especially when, as I said, there's not really any way to know whether or not you're a good peer reviewer, and no system for improving if you aren't. There's some evidence that, at least in the medical field, the quality and usefulness of reviews actually goes down as the reviewers get older. Nobody knows exactly why that is, but it could have to do with the lack of training and follow-up, the tendency to get more set in our ways as we age, and/or reviewers simply feeling burnt out and too busy. It's also worth noting that peer review is really not set up to catch deliberate fraud. If you fake your results, and do it convincingly, there's not really any good reason why a peer reviewer would catch you. Instead, that's usually something that happens after a paper has been published—usually when other scientists try to replicate the fraudster's spectacular results, or find that his research contradicts their own in a way that makes no sense. If a paper isn't peer-reviewed, does that mean it's incorrect? Technically, no. But, here's the thing. Flawed as it is, peer review is useful. It's a first line of defense. It forces scientists to have some evidence to back up their claims, and it is likely to catch the most egregious biases and flaws. It even means that frauds can't be really obvious frauds. Being peer reviewed doesn't mean your results are accurate. Not being peer reviewed doesn't mean you're a crank. But the fact that peer review exists does weed out a lot of cranks, simply by saying, "There is a standard." Journals that don't have peer review do tend to be ones with an obvious agenda. White papers, which are not peer reviewed, do tend to contain more bias and self-promotion than peer-reviewed journal articles. You should think critically and skeptically about any paper—peer reviewed or otherwise—but the ones that haven't been submitted to peer review do tend to have more wrong with them. What problems do scientists have with peer review, and how are they trying to change it? Scientists do complain about peer review. But let me set one thing straight: The biggest complaints scientists have about peer review are not that it stifles unpopular ideas. You've heard this truthy factoid from countless climate-change deniers, and purveyors of quack medicine. And peer review is a convenient scapegoat for their conspiracy theories. There's just enough truth to make the claims sound plausible. Peer review is flawed. Peer review can be biased. In fact, really new, unpopular ideas might well have a hard time getting published in the biggest journals right at first. You saw an example of that in my interview with sociologist Harry Collins. But those sort of findings will often published by smaller, more obscure journals. And, if a scientist keeps finding more evidence to support her claims, and keeps submitting her work to peer review, more often than not she's going to eventually convince people that she's right. Plenty of scientists, including Harry Collins, have seen their once-shunned ideas published widely. So what do scientists complain about? This shouldn't be too much of a surprise. It's the lack of training, the lack of feedback, the time constraints, and the fact that, the more specific your research gets, the fewer people there are with the expertise to accurately and thoroughly review your work. Scientists are frustrated that most journals don't like to publish research that is solid, but not ground-breaking. They're frustrated that most journals don't like to publish studies where the scientist's hypothesis turned out to be wrong. Some scientists would prefer that peer review not be anonymous—though plenty of others like that feature. Journals like the British Medical Journal have started requiring reviewers to sign their comments, and have produced evidence that this practice doesn't diminish the quality of the reviews. There are also scientists who want to see more crowd-sourced, post-publication review of research papers. Because peer review is flawed, they say, it would be helpful to have centralized places where scientists can go to find critiques of papers, written by scientists other than the official peer-reviewers. Maybe the crowd can catch things the reviewers miss. We certainly saw that happen earlier this year, when microbiologist Rosie Redfield took a high-profile peer-reviewed paper about arsenic-based life to task on her blog. The website Faculty of 1000 is attempting to do something like this. You can go to that site, look up a previously published peer-reviewed paper, and see what other scientists are saying about it. And the Astrophysics Archive has been doing this same basic thing for years. So, what does all this mean for me? Basically, you shouldn't canonize everything a peer-reviewed journal article says just because it is a peer-reviewed journal article. But, at the same time, being peer reviewed is a sign that the paper's author has done some level of due diligence in their work. Peer review is flawed, but it has value. There are improvements that could be made. But, like the old joke about democracy, peer review is the worst possible system except for every other system we've ever come up with. If you're interested in reading more about peer review, and how scientists are trying to change and improve it, I'd recommend checking out Nature's Peer to Peer blog. They recently stopped updating it, but there's lots of good information archived there that will help you dig deeper. Journals have also commissioned studies of how peer review works, and how it could be better. The British Medical Journal is one publication that makes its research on open access, peer review, research ethics, and other issues, available online. Much of it can be read for free. _____________________________________________________________ The following people were instrumental in putting this explainer together: Ivan Oransky, science journalist and editor of the Retraction Watch blog; John Moore, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Weill Cornell Medical College; and Sara Schroter, senior researcher at the British Medical Journal. Image: Some rights reserved by Nic's events |

| Posted: 21 Apr 2011 10:34 PM PDT Paper artist Taras Lesko created this enormous 750-piece papercraft model of an Audi A7: Graphic design artist Taras Lesko designed 750 model pieces out of card stock using 285 pieces of paper. He then printed, folded and glued together. Using just a laser printer, two desktop cutting plotters, glue and an X-ACTO knife, in about 245 hours, he had made a car.Audi A7 Made of Paper (via Neatorama) |

| You are subscribed to email updates from Boing Boing To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

Solorza is a cousin of the alleged victims, who emigrated from Mexico. The father of four said three Norteno gang members had put him up to the scam.

Solorza is a cousin of the alleged victims, who emigrated from Mexico. The father of four said three Norteno gang members had put him up to the scam.

I am the son and grandson of helpless, hardcore, inveterate punsters, and when I got to Milo getting lost in The Doldrums where he found a (strictly analog) watchdog named Tock, it was probably already too late for me. I was gone on the book, riddled like a body in a crossfire by its ceaseless barrage of wordplay--the arbitrary and diminutive apparatchik, Short Shrift; the kindly and feckless witch, Faintly Macabre; the posturing Humbug, and, of course, the Island of Conclusions, reachable only by jumping. Puns--the word's origin, like the name of some pagan god, remains unexplained by etymologists--are derided, booed, apologized for.

I am the son and grandson of helpless, hardcore, inveterate punsters, and when I got to Milo getting lost in The Doldrums where he found a (strictly analog) watchdog named Tock, it was probably already too late for me. I was gone on the book, riddled like a body in a crossfire by its ceaseless barrage of wordplay--the arbitrary and diminutive apparatchik, Short Shrift; the kindly and feckless witch, Faintly Macabre; the posturing Humbug, and, of course, the Island of Conclusions, reachable only by jumping. Puns--the word's origin, like the name of some pagan god, remains unexplained by etymologists--are derided, booed, apologized for.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar